Roads you haven’t

been on yet

"I felt like an arrow that could shoot all the way"

A couple years ago I started taking pictures while I was driving. This is a terrible habit, one I would never endorse, and completely borne of the social media age, with its tug toward performing rather than experiencing your life, trying to pin down exhilaration for later consumption as opposed to enjoying it in the moment, but also: I thought the pictures looked cool.

I was doing this on road trips, when I was by myself, and the roads were so empty that even if I lost control of the wheel (which I never did), I would have only spun out and into myself, a one-car pile-up. I texted the pictures to friends, which made me feel less alone, like my view was shared, although the lens had a way of flattening the landscape, rubbing out the magic by at least a third, like a blurry dot on a black canvas when you were trying to photograph the full moon.

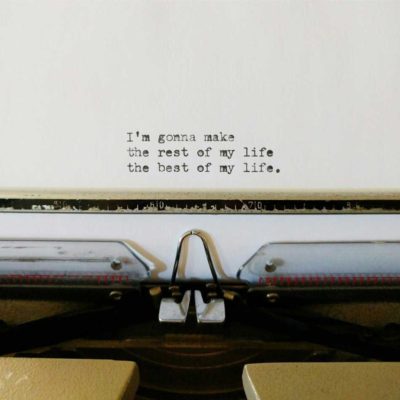

I found something very satisfying about the clean lines and hypnotic geometry, though: A road you have not been on yet. A story still untold. There is a visual in the 2012 movie version of On the Road that makes this point exactly. The character of Jack Kerouac is staring down the unfurling highway in his 1949 Hudson Commodore, and the image fades — so perfect it’s almost eerie — into the close-up on a typewriter ribbon poised over a blank piece of paper. We watch as the key hurtles upward and thwacks onto the page. One more journey.

This is not the actual picture, but it looked something like this:

The movie made little impression on me, but that image sure did, and I often think of it when I’m driving long stretches of asphalt. It’s particularly fitting for a writer so eager not to break the electric current of his creative process that he clickety-clacked his tale onto twelve-foot long scrolls, so that his novel unspooled like the American highway itself. “I felt like an arrow that could shoot all the way.”

A few years ago, I read one of those buzzy pieces where writers share the most embarrassing books they once loved, and no fewer than five guys chose On the Road. Only Ayn Rand received as many votes. I suppose it’s inevitable that a book wildly overpraised by one generation would become a book wildly reviled by another, but the list made me sad. On the Road has problems, for sure, but seeing Kerouac chucked into the scrap heap over and over was like watching a kid throw an old beloved teddy bear in the Dumpster because it’s missing an eye now.

John Jeremiah Sullivan basically makes this same point when he chooses On the Road: “Some books were written especially for young, pretentious people — Look Homeward, Angel is another — and they have their own strange greatness, one that in order to live requires you leave it behind. What they show us about the evolution of personal taste counsels greater skepticism toward future judgments.”

We change. Our loves change. Our lives change. But there’s nothing embarrassing about that.

I didn’t mean to write a blog post about Kerouac, but I guess that’s what happens when you sit down in front of an empty screen with little idea of where you’re headed. That is the exhilaration, the maddening improvisation, the magic trick of the written word: You start typing, and sooner or later, a story comes out.