Why I’m Doing a Podcast

on the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

For most of my life, they were just images to worship or disdain or ignore -- but they're one of the great and complicated stories to come out of my city

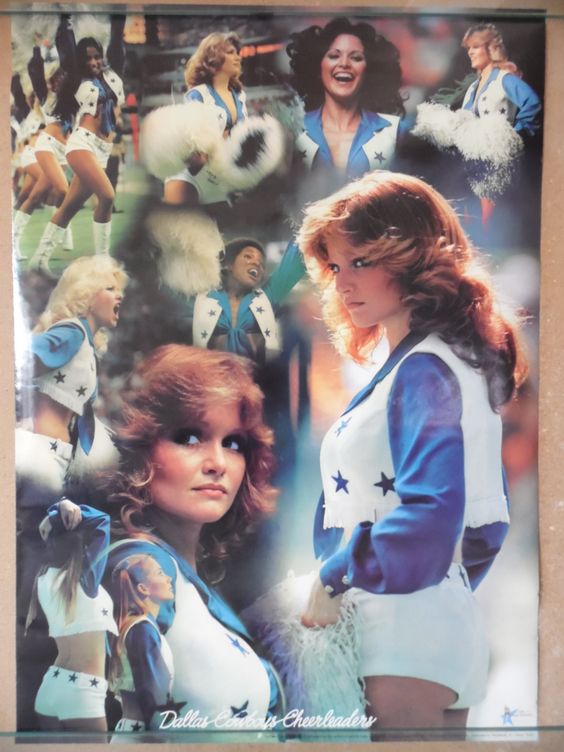

1979 Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader poster, clockwise from top left: Susan Jones, Suzette Scholz, Syndy Garza, Sherrie Worthington, Suzette Russell, Tami Barber, Shannon Baker, and (center) Jill Waggoner.

I grew up watching women’s bodies. I think it started on movie screens, but it moved to television and locker rooms and swimming pools. I watched their suntanned shoulders in halter tops, I studied the parting waves of their tumbling hair, and I wondered if my body would ever have that kind of magic.

There was this poster I was obsessed with at the age of five. I stared at that image on bedroom walls and 7-11s, where Slurpees were medicine for the Texas heat. It was all these women in a blue and white uniform, but the one I couldn’t take my eyes off was the redhead on the right. She had the mane of a lioness, a look of fire — and I saw in her something like the woman I wanted to be.

This was 1979 in Dallas, Texas, where my bookish family had recently moved from Philadelphia. It was a year after a soapy drama called Dallas debuted on prime time, a year after an NFL highlight reel dubbed the Cowboys America’s Team. You could call this Peak Dallas.

In other towns, at other times, I might have grown up staring at royalty or beauty pageant queens. But in the blackland prairie of North Texas, in the late Seventies, I grew up watching the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.

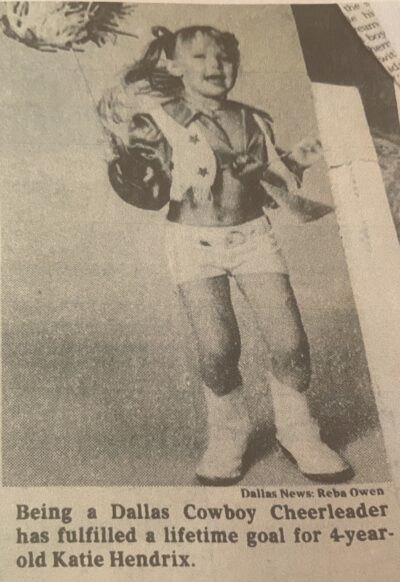

The Little Miss Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader pageant launched in 1979, with 10,000 entrants, including this cutie pie (from the Dallas Morning News)

I spent much of my young adulthood living outside Dallas. I let other climates erode my teen habits of shopping and beauty counters. I wore flip-flops and a gray hoodie to the office of a newspaper, my hair pulled back in a sloppy bun. But about ten years ago, I moved back, and things I’d never noticed before began to fluoresce.

I was standing in a parking lot off the roaring highway when I looked up and saw her on a billboard: That same blue and white uniform, hair like Venus on the half shell, one arm casually draped atop her head. A goddess floating above the lumpen masses so painfully earth-bound on Central Expressway.

Forty years had passed since I first fell in love with the cheerleaders. Empires had crumbled, industries had dissolved. How was it possible so much had changed — and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders were still here?

Stories begin like this. You just — notice a thread, and keep tugging. What struck me in that moment is that I knew next to nothing about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. How they started. Who those women were, what their names or inner dramas might be. They were just bodies. Images to worship or ignore or disdain, and by the time I stood in that parking lot, I’d done all three.

And so I began tugging. I learned the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders had pioneered the spectacle of sexy sideline dancers. Huh, I didn’t know that. I watched their reality show “Making the Team” on the cable network CMT, expecting to be either annoyed or bored, and I found myself wiping tears when the squad was announced, and practicing my high kicks in my bedroom. The cheerleaders may have started as a way to attract a male audience, but the reality show had reshaped them to attract a female audience. Women like me love this stuff: The artistry of performance and competition and personal styling. I could not get over the marvel of their bodies — the arabesques, the jump splits, the way they danced with their hair, almost as though their hair were a fifth limb.

To be fixated on women’s bodies might sound pervy, but to me it only felt logical. I was a little girl who loved dance, but I’d spent an adulthood hunched over a laptop, locked in my human suit. I still saw in those women something I wanted to be.

In 2014, two cheerleaders with the Oakland Raiders filed a wage-theft law suit. Over the next years, law suits moved like a stadium wave across the NFL cheerleaders. Sexual harassment, verbal abuse, body shaming. In 2018, the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders got a fair-pay law suit of their own. It was filed by a three-year veteran named Erica Wilkins. She’s actually the cheerleader two photos up, who’d been featured on the cover of the swimsuit calendar. Even their golden girl turned against them.

I’d grown up in a media landscape where cheerleading was portrayed as a glossy fantasy, and I found myself in a media landscape where cheerleading was portrayed as a waking nightmare. “A Ponzi scheme in hot pants” according to Deadspin. “What fresh hell is going on with the NFL and its treatment of its cheerleaders?” asked Vogue. There were stories of humiliating “jiggle tests” and rule books lousy with double standards. The pay was terrible, even if hundreds (and sometimes thousands) of women were still lining up for it. Media responses moved in opposite directions: These women were elite performers who should be paid according to their value; and this was a silly, sexist tradition that needed to be shut down.

Squads began folding, going coed, becoming more modest. I could never get my hands around what to say about this. So much of journalism (so much of culture) felt like being shoved into the corner of pro or con. Are you for this, or against this? I didn’t know! What I knew is that I’d grown up wanting to find myself in the macho world of men’s sports, that female beauty and movement is one hell of a tractor beam, that I’d idolized those women once and it felt rather disloyal to turn on them now, and that the entire spectacle felt increasingly phony and outdated. And so my love was quite complicated, although when it comes to real love, an honest brokering — I’m not sure there is any other kind.

One day, about a year ago, I was tossing around ideas for various projects with my editor at Texas Monthly. I was slowly working through a revision of my second memoir, but I needed something completely different. He’s the one who came up with it.

“What about a podcast on the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders?”

This was once my closet, and that uniform is a knock-off I bought from an online depot in China, and those shorts are roughly the size of a hand towel.

I almost didn’t take on this project. Much of my work comes from personal experience, and I had no experience as a cheerleader or dancer, not even in high school. I was only a fan of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (when I was five!), but the more I learned, the more convinced I became that they were one of the great stories to come out of my hometown, and not enough of that story was known. I read Joe Nick Patoski’s epic history of the Dallas Cowboys (highly recommend), and I flipped through the 70-plus pages of source articles and books on the football team, and I saw exactly one book about the cheerleaders, Decade of Dreams, which was out of print.

Everyone had opinions on the cheerleaders — pro or con! idolize or disdain! hot or not! — but I wanted to tell the story of their evolution from a sideline experiment to a global phenomenon, moving from a culture very skeptical about the display of women’s bodies, through decades of rampant sexualization, and back to the beginning again, as a new skepticism takes hold. It’s a story about exploding taboos and also reinforcing traditional ideas at the same time. There is a terrific 2018 documentary about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders called The Daughters of the Sexual Revolution. Directed by Dana Adam Shapiro (who also did Murderball), the movie is a rocket ride through the squad’s golden era, but my biggest gripe about that film is that I wanted it to be about six times longer.

And so, as the narrator says in her smoothest contralto, my journey began. It was a journey that would take me across the past 50 years of history — across changes in women’s lives, in media, in the city of Dallas and the country itself. It would take me to the rubble of Texas Stadium and the consumer coliseum of Cowboys stadium, aka JerryWorld, where the American flag is displayed above the logos for Pepsi and Miller Lite.

Left: The old site of Texas Stadium, longtime home of the Cowboys. Right: The enormous AT&T Stadium built by Jerry Jones, a cathedral to football and corporate sponsorship.

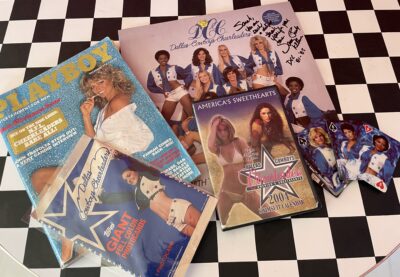

The journey would take me into cheerleaders’ homes, where memorabilia was often spread across a dining room table like a grand buffet. It would take me through lore about strippers, and scandals, and personal sacrifice. It would take me into YouTube rabbit holes and the deep oceans of eBay, where my purchases include: a 1981 deck of playing cards, a 1982 vinyl album of workout routines, a 2005 swimsuit calendar making-of DVD, and a 1978 Playboy.

Artifacts of study.

The Dallas Cowboys politely passed on this project. Those were the words I got in an email. “We are going to politely pass,” and the polite part seemed a matter of opinion, but OK. I did speak to about 30 cheerleaders from the past half century, and about a dozen of them appear in the podcast, alongside historians and cultural critics, but the cheerleaders carry this story. They talk about things many of us face — a search to discover their own talent and feel special, a struggle with their bodies, a hope that they can balance the inevitable frustrations and criticisms of an experience with the enormous gains they got, a frustration when their contribution is not valued (sometimes monetarily, sometimes in the public perception), a craving for the spotlight and the challenge of that scrutiny, a desire to be sexy but not just sexy.

Some of those conversations lasted five and six hours, and over the past months, as I labored to assemble an eight-episode podcast (with much help from my Texas Monthly team), I found myself overwhelmed at how big this project was and also frustrated by how much I had to edit, condense, and skip. Sometimes I feel like I still can’t get my hands around this thing.

But I never got tired of talking to the cheerleaders. There was often this moment, at the start of our interview.

“So is this a video?” they’d ask, watching me assemble the metal cranes of sound equipment.

“No, this is audio only.”

“Oh good.” And I could feel them relax, and they’d sit however they wanted in the chair, and not worry if they were wearing lipstick or their hair was a little messy.

“This,” I’d say, taking a seat across from them, “is about your voice.”

AMERICA’S GIRLS is an eight-part podcast. You can listen here.