The Impossible Year

Confessions of a lucky but miserable person at a rather unlucky time

On the site of the once-great Texas Stadium in July 2021, before things went south for me.

I had a hard year. A lot of people had it harder, a fact I reminded myself of constantly. I never got Covid. Nobody in my family got Covid. I had a solid roof, a warm bed, a loyal and outrageously handsome cat, and a series of microwaveable Amy’s frozen dinners that people in other parts of the world might find very luxurious. And yet, the year was hard, and knowing how much worse other people had it never made it better. It made me feel guilty, actually, because here I was — not sick, not forced to home-school my kids while juggling a demanding job, not tirelessly slogging through the bleak corridors of a hospital to tend to one more doomed patient, not even forced to roll the corn tortillas filled with sprinkled cheddar to enjoy a delicious cheese enchilada — and everything still sucked.

“I think I’m having a meltdown,” I told friends during the worst stretch, from August to late October.

“A lot of people are struggling,” they often said, and it was meant to be grounding. It was meant to remind me I was not alone. One more wounded soldier in the vast limping army. But I would start doubling back, embarrassed not to have earned my place. (“I know I’m fortunate,” etc. etc. ) Then my friends would start scrambling to validate my particular suffering. (“Everyone’s challenges are unique,” etc. etc.) And we’d fall into this gentle tug of war that made me sadder, so I didn’t talk to people much. I flaked on lunch dates. I deleted my dating apps. I disappeared from social media.

People only wanted to help. I only wanted to be helped. But such was the poignant disconnect where I found myself stranded in the fall of 2021. It was easier to be alone.

Wallace, a loyal and outrageously handsome cat.

The problem was work. The problem was that I couldn’t sleep, and I woke in the dark hours with an anxiety so full-throated my body was trembling, and it didn’t stop trembling as I trudged from station to station through the afternoon. The problem was that I could spend an entire day writing two sentences, and I know that sounds like an exaggeration, so let me assure you it was not. One day, two sentences. I hadn’t experienced this kind of writer’s block (or whatever you call this) since my mid-twenties, when I’d pace and smoke, trying to shake loose a few strong verbs. Back then, I drank to quiet the anxiety. Now, I was more than ten years sober, and I refused to drink — but what could I do?

People told me it was hormones. People told me it was depression. People told me it was a painful but necessary transition phase — but from what to what? I tried supplements. I tried exercise, until I stopped exercising. I was flat broke by this point, and the specialists and spa trips and vacations that might have helped at another time were out of reach for me. (Also, there was a pandemic.) I borrowed money from my parents. I borrowed money from my brother. I borrowed money from a good friend. Not for indulgences; for rent. I borrowed money the way I used to buy booze, a little bit from a few places so no one one would know how bad things had gotten. I started smoking again. I paid for the cigarettes with a gift card from American Express I found lying around. It was stupid, and I didn’t care.

One low afternoon, I collapsed in the padded chair of a twelve-step meeting and sobbed during my five-minute share. Afterward, a gray-haired woman with a maternal figure took me to dinner, and she told me to pray (thanks), and she handed me a pamphlet like a goddamn newcomer, and I felt a seizing despair that this stranger was spending so much time with me, and I only wanted to flee.

“Would you like a Buddha?” she asked as we parted, pulling out a chubby golden trinket from her purse.

“Yes,” I said, and I rubbed his round belly with my thumb, and I placed the goofy Buddha figurine by my bedside table, and actually, the Buddha helped. I smiled whenever I saw it.

But I was worried I would not make it through this wicked passage. I stopped writing in my journal. I stopped reading books, and then I stopped reading the news. I couldn’t watch Netflix. I didn’t even listen to music. It was a very boring time. I mostly stared and paced. I was starting to retract from job offers, panel offers, I tried to get out of the work I’d already taken on, and if I did this, if I actually quit writing as I fantasized about daily, I had no backup plan, no way to pay my bills, which was equally harrowing. One day I applied to be a Door Dash delivery person. It seemed like a gig I could manage. Almost immediately I got an email that there was a waiting list.

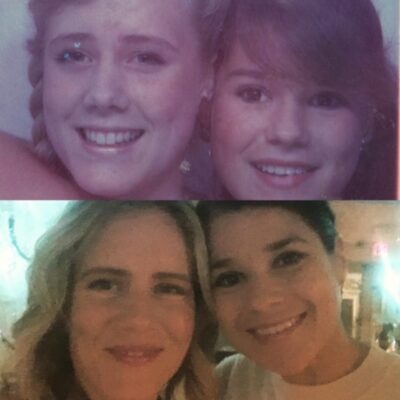

I met my friend Mary in sixth grade. People often mistake us for sisters, and maybe that’s not a mistake.

And so, I did what all of us do when faced with the impossible — I soldiered on. Weekends were particularly rough, because even though I dreaded the Zoom meetings and the knock-knock-swoosh of the Slack channel, those obligations anchored me. The weekends left me drifting in the poison waters of my own worst-case scenarios. My friend Sharon, who knew this about me, made a point to see me each weekend, even though she was a busy columnist. We sat across from each other at burger joints and a Mediterranean restaurant (she picked up the bill), and she helped me strategize the upcoming week. My friend Mary, who also knew this about me, made a point to show up to my place on Saturday mornings, even though she was busy helping her mother move into a retirement home. We took long walks on the tree-lined streets, both of us wearing hoodies, the same height, the same size and coloring and blonde hair, looking like sisters, and sometimes I cried when we got to the part where I was supposed to talk.

“I have total confidence you’re going to get through this,” she told me.

“But what if I don’t?” I asked.

“Then borrow my confidence,” she said, and I squeezed her hand.

These stories make my eyes water, not because they make me feel sad, but because they make me feel lucky. I have always wanted a partner. I have always wanted a husband and kids and the kind of connected domestic life that seemed a birthright to a little girl growing up in the Eighties, and I didn’t have any of those things, which also amplified the sorrow (and relief, depending on the day). But I had these women. Some of my friends are guys, and they helped too, but really? This year? It was the women who saved me.

My friend Jamie, who called on her long walks. My friend Julie, who called on her long drives. Those two know me better than most living humans, and I never had to pretend with them, which was a gift. My friend Sunny, my friend Andrea, my friend Amy, who also happens to be my agent. The legacies: Lisa, Stephanie, Tara, whom circumstance kept far away this year though they still felt close. Victoria, Pia, Carey, Eleanor, Amanda, Tracy, Deborah, Allison, Kim, Nicole, the other Amy, I’m fortunate to have so many friends, I’m certain I’m forgetting someone (and I apologize). But I could not find my way out of this hole.

Austin, TX, 1992. Julie and I were taking selfies before that became a word, back when you had to walk a mile in the snow just to turn a Canon camera toward your face.

One Sunday, as I sat chain-smoking on a couch I’d placed in an outdoor corridor, staring at two fold-out chairs I never used, I texted my friend Pam. “I think I’m having a meltdown. Can you talk?” She could, even though if memory holds, her son was having his birthday party in the other room. I told Pam I wanted to quit. Everything. The creative life I had fought for all my life was proving too much; I was overmatched. Pam is one of those wildly successful journalists who struggles more than outsiders might imagine, and I knew she’d understand. She listened. She shared her thoughts. “I don’t think I’m helping,” she said, but she was. Maybe she meant she couldn’t fix it. But only I could do that.

It’s very scary to have built your life around work, and then watch the work crumble. I wouldn’t recommend this route. I needed a hobby. I needed a purpose. I needed something.

The next weekend, I went to visit my friend Jennifer, who had moved to a ranch near Corsicana, an hour south of Dallas. I sat on her porch staring out at the big tree with its strong, low-swooping branches and the dogs curled on the grass, and I felt something closer to calm. Jennifer and I became friends in eighth grade, two bookish middle-class kids in a rich neighborhood, but she’d made her own sizable income as a veterinarian who co-owned three successful clinics. When I told her I dreamed of quitting but had no idea how to pay my bills, how to survive, she said that was OK, she’d support me. Jennifer has two teenagers, four horses, a handful of goats and donkeys and fat waddling hogs, but she would make space for me. We scoped out the one-room lake-house near the water that she was currently renovating, and we wondered aloud if my cat would fit.

Jennifer and I in a photo booth in ninth grade (top), and Jennifer and I at a fancy hotel on Christmas Eve, 2017.

But I did not move into Jennifer’s place. I did not quit, at least not for long. I got on Zoloft, which is a thing I very much did not want to do, and I did it anyway. I told my colleagues that I needed their help, and they happily gave it to me. The Zoloft was slow to kick in, and for a month I couldn’t tell the difference, but one week I read Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads in three sittings, which was like slipping underneath the soft weighted blanket of someone else’s struggles, and the next week I listened to the audiobook of My Dark Vanessa (also recommend) as I walked around White Rock Lake, and I could feel the clouds starting to part. This was good. I liked reading again.

I can’t pinpoint the day things got better. It was like recovering from heartbreak, or a nagging cough, everything was miserable and then slowly, almost imperceptibly, I felt released. I wasn’t trembling anymore. I was cracking jokes on my Zoom calls, I was smiling even when I didn’t have to be. I was making deadlines, going to movies, posting pictures of my cat on Instagram. The work I was convinced would be too much for me stopped feeling daunting and started feeling invigorating. One morning, I woke up in the dark hours, opened my laptop, and a thousand-word essay popped out.

And so I end 2021 in a much better place than where I spent much of it, which might be all you can ask. I am grateful for my friends, grateful for my work, grateful for the pharmaceutical intervention I really did not want, but that’s the story with life sometimes, you need things you don’t want, and you want things you don’t need. I am too allergic to sunny optimism to believe the next year will be better simply because it is next, but I know this.

You can always make a new start.

This is a picture of a donkey eating my car at Jennifer’s ranch. May we all find comfort and companionship in 2022. We’re in this together.