Things Fall Apart:

Thoughts on Joan Didion

On the master of precise prose, falling in love, and writing as an irrelevant act

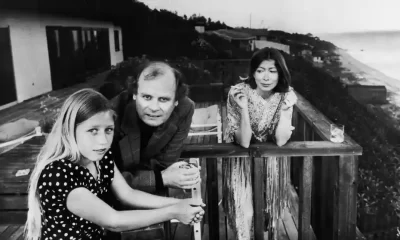

Joan Didion, 1934-2021

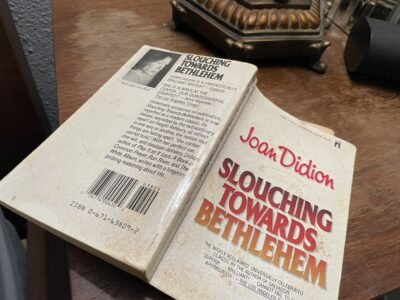

My college boyfriend introduced me to Joan Didion. He gave me his dog-eared paperback of Slouching Toward Bethlehem. I remember turning to the picture of Joan on the back, young and pretty and serious. I remember the poetic allusion of the title that was lost on me, because I never read poetry.

“I really think you’ll like her,” he said, and I nodded.

I’d wanted to be a writer since I was eleven. Maybe earlier, but definitely eleven. That’s the year I won a writing contest, and the teachers and the kids swooned in a way that was nearly dangerous, because it instilled a blazing entitlement. Of course I won the English award in eighth grade. Of course I got A’s on my essays in high school English, even though I never read the books, which I considered boring. I was obsessed with Stephen King, and Edgar Allan Poe, and William Faulkner, whose twisted Gothics made me weirdly horny even as they barely made sense.

By the time I got to college, and found myself at long discussion tables with other precociously talented students, I was starting to realize this approach had been a mistake. My friends talked about authors I did not know: Tom Robbins and Franz Kafka and Hunter S. Thompson. Loving Stephen King was such a cliche, painfully middle-brow, and I badly wanted to up my game, but I found the introduction to this new female writer kind of threatening. Was she better than me? Did my boyfriend like her more? Was he sorry he wasn’t dating Joan Didion?

That guy was a wanderer. A chef, who carried knives in his car, and rolled his own cigarettes, and liked going on road trips and stopping at dives where the sad women with coffee pots wore too much blue eyeshadow. I never felt cool enough for him. Once I found a picture of his friend Patricia in his wallet. That was weird. She lived in New York City, a place I’d never been. “I really think you’d like her,” he told me, even after I found her cotton panties in his closet, but I didn’t think I’d like Patricia, and I didn’t think I’d like Joan Didion.

“Thanks,” I told him, placing Slouching Toward Bethlehem on my bookshelf with zero intention to read it.

I was 25 when I first opened that book. I was working at an alt-weekly newspaper in Austin, surrounded by more people whose vast knowledge of art and music intimidated me, and I was trying to finish a big story I badly wanted to write and now badly wanted to quit. It was always this way with me: If I didn’t get the splashy assignment, I’d fume with envy, but if I did get it, I’d become crippled by self-doubt. I’d spent a long weekend staring at a blinking cursor, pushing around two sentences like lima beans on a plate, pacing the backyard as I chain-smoked Camel Lights, or Marlboro Lights, or whatever I was smoking back then. Writing, which had once been exceedingly easy, had become more like running in tar.

I don’t know why I picked up Slouching Toward Bethlehem. Maybe someone mentioned Joan Didion. Maybe nobody had. But I opened to the preface, and this is the part that struck me:

I am not sure what more I could tell you about these pieces. I could tell you that I liked doing some of them more than others, but that all of them were hard for me to do, and took more time than perhaps they were worth; that there is always a point in the writing of a piece when I sit in a room literally papered with false starts and cannot put one word after another and imagine that I have suffered a small stroke, leaving me apparently undamaged but aphasic.

It was starting to sink in that writing was a thing I’d have to work for. It would require me to read everything, even books I did not like, it would require me to sulk and fret and tremble with fear not because writing was hard (though it could be), but because writing mattered. I had to fight for it.

But I’d never seen a writer describe my own particular agony with such a direct hit. I felt the same way I had when that swaggering college boyfriend first drizzled his fingers down my bare back with a stroke so masterful that all I could think was: Yes. Yessss.

I guess falling for a writer isn’t so different than falling for a guy, at least for me, except that guy bailed after six months, and that dog-eared Joan Didion book — well, it’s sitting face-down on my chest I as type this.

I moved to New York City, a place that Joan Didion had captured in her lasso. “It is often said that New York is a city only for the very rich and very poor. It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city for only the very young. “

I was 31 years old when I found my first place in Brooklyn, an age that strikes me as dewy with innocence now, but I did feel old among the visual arts students and trust funders of South Williamsburg. But the city was filled with so many cool spots, and being inside them made me feel cool, too.

A dear and very connected friend used to get us reservations at a swank speakeasy in the theater district, with dim lighting and zebra-print chairs and $16 glasses of Malbec. One late night, while smearing brie onto a hunk of rustic bread, I looked over at a leather booth and saw Joan Didion. I recognized her immediately: The pageboy hair, the big sunglasses, a slump that was maybe more like frailty. She was seated next to a distinguished man I would learn was the director David Hare. They’d recently debuted the one-woman show of her memoir The Year of Magical Thinking on Broadway, and even though I was broke all the time, and even though I was homesick for Texas, I thought to myself: This is why I can’t leave New York.

I also thought, “Oh my God, she is TINY.”

I am 5’2″, a height that has only intimidated small children. I hated being short, but Joan Didion used to say her stature was an advantage, because people told her everything. They misjudged her as weak; meanwhile, she was super-recording whatever they said. Her insistence on writing from an intimate perspective, a habit I could not quit if I tried, seemed only honest, maybe admirable. That astonishing memoir, and her trove of wisdom during the decades when America seemed to be cracking, quickly made her one of my go-to writers.

Of course I did leave New York. I moved back to Dallas, a rather uncool place though it suited me, and over the past ten years, when people asked my favorite authors, I usually said Joan Didion. That had become a cliche, too. Joan Didion was a style icon, a literary legend, a figure of dignified suffering, who had lost her husband and daughter within the space of two years.

She never did write a classic novel, like so many of her peers. Play It As It Lays is icy and atmospheric, but I don’t remember much of it. Those essays, though. She made personal writing feel journalistic, and journalism feel personal. She made catastrophic events feel survivable, and ordinary events feel momentous. Feminist types liked to quote her in social media posts and stories, even though she wasn’t so hot on feminism. (“The astral discontent with actual lives, actual men, the denial of the real generative possibilities of adult sexual life, somehow touches beyond words.”) But with her fierce economy of language, and her chic author’s photos, she was Instagram cool long before Instagram ever existed.

A male writer once challenged me. “Who’s your favorite female author? Don’t say Joan Didion.”

The pinwheel in my mind spun, as I cast about for a runner-up. “Janet Malcolm,” I said, and I did love Janet Malcolm, but it was like saying your favorite band was The Who because you didn’t want to say The Beatles. Leslie Jamison, Rachel Cusk, Cheryl Strayed, their words gave me the falling-in-love feeling, but Joan still felt like the original. The taproot.

In 2017, the Joan Didion documentary The Center Will Not Hold came on Netflix, and I watched it several nights in a row for weeks. I was having trouble sleeping, and I would wake up at 2am, and start the film in the dark, with its dazzling opening shot of the San Francisco bridge and those famous lines from Slouching Toward Bethlehem.

I went to San Francisco because I had not been able to work in some months, had been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act, that the world as I had understood it no longer existed. … It was the first time I had dealt, directly and flatly, with the evidence of atomization. The proof that things fall apart.

But there was this one line I gnawed on for months. She was talking about her husband John Gregory Dunne, also a writer (I should probably read him), and even though I knew very little of their lives except the glimpses I got in her work and her photos, I considered them a model couple. Glamorous, brilliant. Partners.

“Falling in love was not in my vocabulary,” she said.

Could that be true? The woman with words at her fingertips said “falling in love” was not in her vocabulary, but in mine, it was a mainstay. I’d been chasing that feeling across so many decades, so many time zones, and I started to wonder (not for the first time) if I’d been doing it wrong.

Joan Didion was practical. She was unsentimental. I was deeply sentimental, terribly impractical. Maybe that’s why I needed her. Not just for the inspiration, but for the corrective.

Once, in a dry season, I gave a Joan Didion book to a man I loved. (Well, actually, it was a link to an essay, but that sentence sounds lame.) He fell for her instantly, as I knew he would.

“There will always be an asterisk next to her name that makes me think of you,” he told me, which made me proud and sad at once. Proud because being roped to Joan Didion was a writer’s dream, and sad because the sentence forecast a time when we would not be in each other’s lives, which proved to be prescient. Things fall apart. I have not spoken to him in years. I couldn’t tell you where he is, what he’s doing, who he loves. But it’s my girlish hope that when he read the news that Joan Didion died at 87, there was an asterisk next to her name that made him think of me.

Is that selfish? Only human? I remember one more line in the preface to Slouching Toward Bethlehem that struck me, one I have quoted over and over these many years.

“That is one last thing to remember: Writers are always selling somebody out.”