Other People’s Postcards

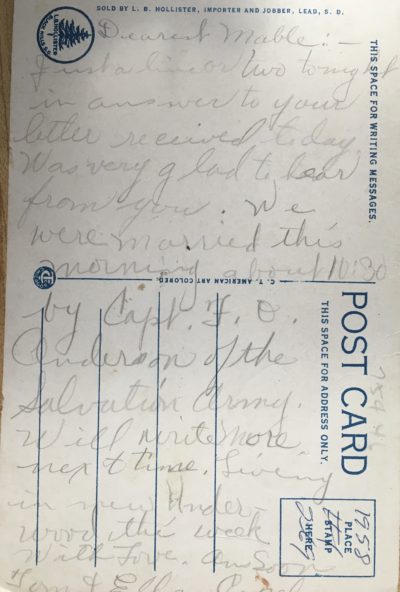

"Dearest Mable, Just a line or two tonight."

Many years ago I began collecting old postcards. I found them in vintage stores, stacks upon stacks of messages once sent, or never written, and I’d settle into an armchair and leaf through them, wafting with the smell of other people’s basements. I never knew what I was looking for, but then something caught my attention.

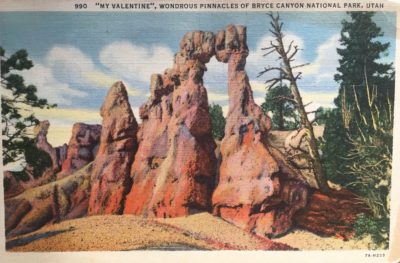

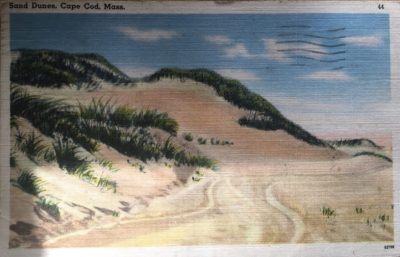

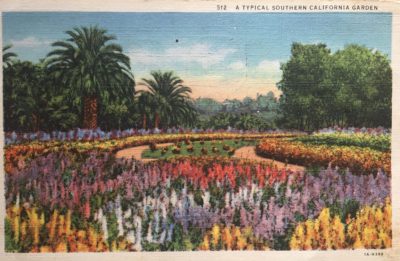

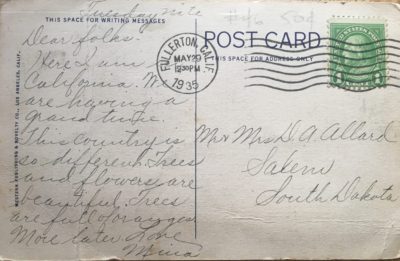

I was drawn to the mid-century postcards with white borders and the clean small font at the top placing a pin in the map. A Typical California Garden: Bit of an oversell for this one, but OK. The pictures looked like photographs that had been painted, usually in pastels more lush than real life (an early Instagram filter, a goosing of reality), on card stock that felt like linen, a gratifying hatching under the fingertips. My eyes scanned for certain details. The delivery stamp marked 1935. A postage stamp that cost a penny. And the unadorned address. No apartment number, no zip code. A world so small that our recipients need only be identified by their name, city, and state, and the resourceful human tasked with delivering this note could find them. (“Oh, the Allards of Salem? Yes, I know the place.”)

I started collecting other people’s postcards around 2002, which was, not coincidentally, also when I began traveling the country alone. I could not have articulated this to myself, but I liked the companionship of the traveler across space and time, that sense of watching someone’s eyes open. This country is so different. I understood the urge to document and share an experience as it passed over your skin. I kept a blog, a platform that was new in 2002 but outdated by 2010, displaced by the social media giants that offered something like postcards sent all day long, to everyone at once, a fusillade of postcards fueled by the same impulse to document and share — this is me now, this is me then, this is what I was thinking, wanna hear? — but maybe it says something about me, or nostalgia, that the old postcards felt special and the real-time social media dispatches felt cheap and performative. It was so easy to post a selfie to Instagram, tap-tap boom, that I had come to admire the mighty odyssey of the humble postcard: A hand plucking the rectangle from a squeaky rotary wheel in a gift store, the dull graphite of a pencil pressed to the glossy white box on the back, the tongue licking the stamp (licking the stamp!), and the arduous cross-country journey — from blue postage drop to flat-bed truck to carrier bag to metal box where a red flag raised to alert the home owner of its presence. All of this work, all of these delivery systems marshaled so that one person could say to another: Trees are full of oranges.

Most messages were mundane. The text limitations of a postcard are punishing (like Twitter’s character count), and many users failed in the face of this challenge. Notes often began by needlessly explaining the picture, as if the card hadn’t done this work, then clarifying the writer did not have time to write, or didn’t have space to write, at which point they were mostly out of room and had to wrap up by announcing their intention to write later. The postcard writers of the Thirties and Forties and Fifties could have used some style pointers.

Every once in a while, I stumbled on a genuine moment.

This one’s hard to read. The money line arrives just prior to that half-way mark.

We were married this morning about 10:30 by Capt. F. D. Anderson of the Salvation Army.

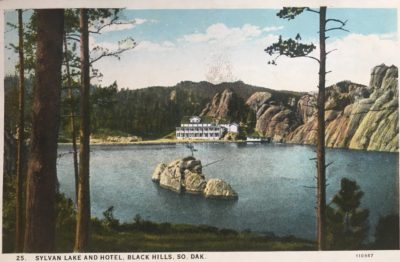

He just pops it in there, like oh right, and another thing. What was going on here? The note cascaded blithely across the address box, leaving the mystery of how the message was sent, and why a postcard had been chosen but its rules not followed, though the front of the postcard offered a clue. It was a fancy hotel on Sylvan Lake in South Dakota, presumably the location of the ceremony and/or honeymoon.

I had so many questions. Who were these newlyweds? Were they still married? Were they still alive? How had I procured two seemingly unrelated postcards from the sparsely populated state of South Dakota? (And who knew South Dakota had a lake?)

Maybe I collected postcards for the same reason I collected stories and books and sepia-toned pictures of strangers. They gave me permission to dream. Permission to step into someone else’s life, or alongside them for a moment. I was seeking the assurance that other people had been here, that other people had wandered and discovered. These were their adventures. These were their announcements (not enough room), their regrets (write more later), their dreams never quite fulfilled. Many of the postcards remained blank on the back.

It was not until writing this blog post that it occurred to me I could Google the author who was married in South Dakota. I could find this mystery man. The internet presented me with a complete narrative arc. Married in South Dakota, died in 1976. He and his wife had six children. I got that tug like maybe the children should have this postcard, but the fact that it was sitting in my hand suggested they did not want it, and so I would hold on to it, never knowing why, or what it delivered to me, but sensing the solemn duty we have to one another, to bear witness, to travel together.