His customary and legendary

range: Larry McMurtry, 1936-2021

The Texas author I had zero interest in for much of my life

Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall in Lonesome Dove

The Lonesome Dove miniseries rolled into town in 1989, when I was fourteen years old.* Back in the before-times of the late Eighties, computers were clunky green-screened things known to your serious nerd variety, and the television was the center of the household. We built cabinets around our televisions, we kept drawers underneath it, in case anything fell out. The televisions were enormous and wide as fish tanks (people actually turned them into fish tanks). There were really only three channels, so if you didn’t like what was on, you could suck it. But most of the time, you did love what was on, because television was designed for mass consumption and maximum pleasure.The funniest comebacks, the most satisfying storylines, the most attractive humans. And onto this pasture, the Lonesome Dove mini-series galloped, with its squinting cowboys and pretty supporting females, and everybody in my affluent Dallas school was watching it — except for me.

I was a TV junkie, but I did not watch Lonesome Dove, and I’m not sure why. Kids at school enjoyed it with their parents, cross-generational bonding over a mythic landscape, but my parents were Philadelphia do-gooders transplanted to north central Texas, and they had little interest in Texas Rangers and dusty Western romance. My mother thought television rotted your brain (which is probably why I coveted it so much). I remember getting grumpy over that show, because people raved about it for years, like a party to which I had not been invited, but the party kept recurring. I babysat in other people’s big two-story homes, and I spotted VHS cassettes of the mini-series lining their shelves. I had no interest. I’d been obsessed with the TV show Fame, until I became obsessed with the TV show 21 Jump Street. Talented kids at a New York magnet school, undercover cops at a Vancouver high school. Just the thought of grizzled old men in cowboy hats made me yawn.

In my twenties, I learned the name of the author of Lonesome Dove, which apparently began its life as a novel. Larry McMurtry. At the alternative paper in Austin where music and movies and books were sacred texts, people had a respect and even reverence for the guy, although it was easy to skate by without ever reading him, the way you can get an English degree these days (PhD probably) without reading Steinbeck. It just doesn’t come up.

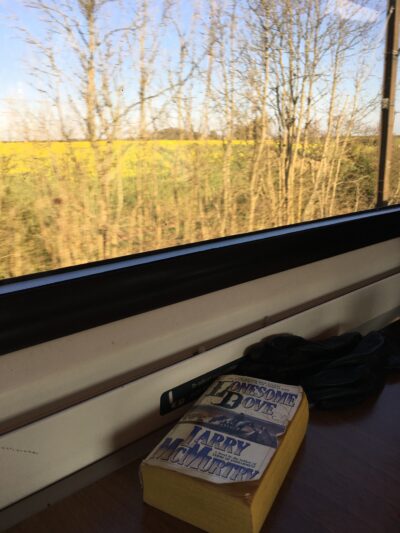

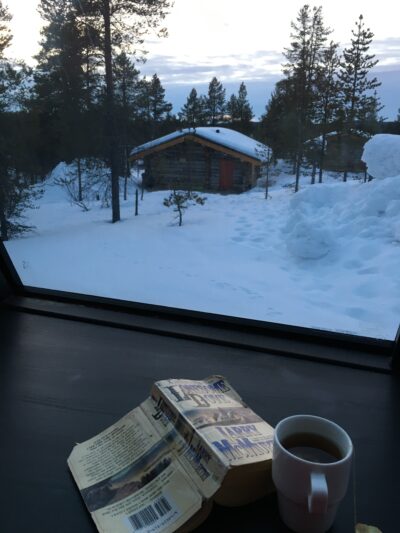

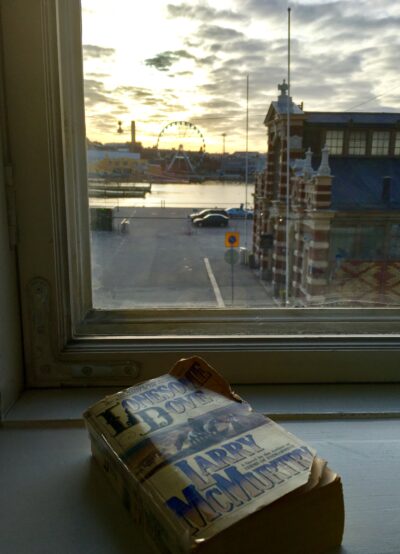

I was in my early forties when I read Lonesome Dove on a very close friend’s recommendation. Actually I watched the mini-series first, which held up powerfully well, despite some questionable mid-Eighties special effects, and it’s a sign of tremendous storytelling that after experiencing six-plus hours of drama on the trail from South Texas to Montana, I only wanted to take the trip again. I read the nine-hundred-page novel on a family trip to Scotland and then Finland, and I was so enthralled by the experience that I kept taking pictures of the book in various locations, posing it like the child or the boyfriend I did not have.

train from Edinburgh to London

Ivalo, Finland

Helsinki, Finland

It’s a mystery why we fall in love with some stories and not others. I can’t tell you the number of much-beloved, critically acclaimed books and TV shows I start and never finish. I just don’t care. I don’t need to take that trip, which is not a judgment on the creator but an expression of something I’m looking for and cannot find.

David Foster Wallace talked about the click you experience with a certain piece of writing, which is as good a description as I could muster. The click happens, or it does not. And as a devoted David Foster Wallace fan, I can assure you many, many people do not feel the click with his work. I’ve stopped telling people Infinite Jest is one of my favorite books, because I’ll be forced to listen to how they didn’t finish it, how their theory is no one actually finishes it (they’re wrong), how pretentious and unwieldy a book it is (did you miss the part where I loved it?). Anyway. I clicked with Lonesome Dove, and I clicked hard. I got mopey near the final chapters, and I wound up in a stupid fight with my brother. I didn’t want the book to end.

Let me flip through my creased paperback and share a few underlined passages at random.

He knew at once that he had forever lost a chance to right himself.

“You know more than you say and I know more than I know.”

The wind was endless and fierce. It renewed itself again and again, curling itself out of the north to take her flowers from her, petal by petal, until nothing remained but the sad stalks.

I loved the characters, even the mean ones. I loved wandering through that pitiless land, how endless the struggle. McMurtry wrote about women with great sensitivity and deep observation. He was not handsome (“he looked like a writer” is probably the kindest description), but I learned from profiles that he dated or was otherwise close to many women. His ability to capture female complication marks him as unusual among the late-20th century giants, many of whom I love but I’d grown accustomed to their clumsy hands. I came of age reading novels by and about men, it never bothered me, and I took it as a given that their portrayals of women were 10-50 percent paler than the male protagonists. Not McMurtry. Everyone had range.

He co-wrote the screenplay for Brokeback Mountain with his writing partner Diana Ossana. It was a movie of tremendous longing, and maybe tremendous longing is the frequency of the song McMurtry was singing that I heard so crystal-clear. I just can’t quit you: That was the money line quoted so often it became a punchline. But its meaning was profound to me, and many others, in a changing world where the land remained pitiless even as it grew more accommodating. At many junctures, in many contexts, I just can’t quit something or the other.

I started plowing through McMurtry after Lonesome Dove. He wrote more than twenty books. All My Friends Are Going To Be Strangers was an early novel about a young writer coming in to his success and sleeping with a bunch of complicated women. (Huh.) I started Terms of Endearment but never finished it, never got far. The other books didn’t have the click. I didn’t fall for the characters in the same full-bodied way.

I liked his essays about small-town Texas in slim collections like Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen and In a Narrow Grave. The essays captured the migration from farm to city that realigned twentieth-century Texas (and America), from horses to trucks, from open fields to barbed wire. He grew up in the rolling prairies, a reader and a thinker who never much belonged, and he became a writer who never belonged in LA or New York or even Austin, which is why he stayed in small-town Texas, despite being the man who wrote so eloquently about its demise, and some part of me felt understood by this dislocation. A person gets forged by a landscape they never wanted and it shapes you so that you don’t fit anywhere else. I just can’t quit you.

Larry McMurtry died last week. He was 84 years old. He lived in Archer City, about two hours northwest of Dallas, the dying town he immortalized in The Last Picture Show, where he ran a book store, the one and only reason most people visit Archer City. McMurtry grew up in a home without books, but he became a rare-book collector. For years I heard stories of book nerds like me traveling to the place, wandering the endless stacks, hoping to catch a glimpse of the man himself. He had a reputation as a crank (maybe he was shy, who knows), and twice over the past years I’ve been on my way to Archer City when plans changed at the last minute. A pandemic struck, maybe you noticed. All the bookstores closed. They closed for so long I got to wondering if they’d ever open again.

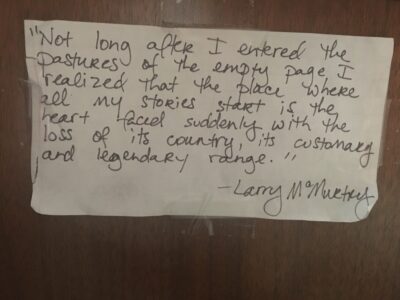

I keep a quote by McMurtry taped on my bedside table. My house is dotted with quotes written on yellow legal paper. They’re meant to inspire me, but often they become invisible, and I forget they’re there until people come over and ask why John Stuart Mill is on my refrigerator, and it’s like: Oh, he is? What did he say? (“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.”) But I kept McMurtry beside me as I slept. I never forgot he was there, never. I read the passage from time to time and was swept away by the rhythm of the language, its easy gallop, how it articulated something I needed to hear but had not known how to say about the book I was currently working on, struggling with, but could not quit.

The heart faced suddenly with the loss of its country.

Its customary and legendary range.

I was sad when Larry McMurtry died, but everyone dies, and 84 years is a good long life. His death made me think of lost prairies and empty pastures and things that never came to pass. I felt a stab of regret I didn’t make it to the bookstore while he was still alive, which hardly makes sense, since I almost certainly would not have seen him. But I wanted the hope and wish of knowing he might be lurking there, hidden in the stacks.

But here is the magical part about writing: He still is.

*I had the year wrong in my original post. I said it was 1985, which is when the novel came out and suggests the kind of deep research I do before blogging. I leave up this mistake as evidence that writers need editors and fact-checkers. We are lost without you.