Nostalgia in the key of metal

A story about lost art, lost loves, and the consumer cycle on constant rotation

The young woman jangling keys to the dressing room is wearing an Iron Maiden shirt. Three items drape over my right arm, all of them designed for her demographic, but that shirt is straight out of mine. My older brother used to listen to Iron Maiden, a blunt counter-point to my Whitney Houston, and the pummeling sounds drifting from his bedroom were the stuff of aspiration and nightmares. Part “I gotta listen to that,” and part “What is wrong with people?”

The dressing room door swings open, and I pause her. “I have to ask. Do you like Iron Maiden?”

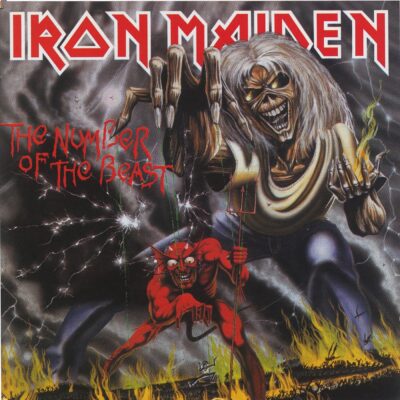

“Oh.” She plucks at the hem of a baseball jersey with a Skeletor figure playing guitar. Iron Maiden album covers were uniquely creepy. I remember shuffling through my brother’s cassette collection, which he kept in a narrow wooden Sound Warehouse crate. Skeletor in a wig, Skeletor with a flag, Skeletor taking a bite of the globe. He had seven or eight Iron Maiden tapes. “No, I haven’t,” she says, looking like she’s been busted.

“My brother loved them.” The angry teen boys of the Eighties would have enjoying seeing a cute girl in the mall in an Iron Maiden shirt. She has that incidental prettiness, ponytail and jeans.

“Cool,” she says, and bounces away.

British artist Derek Riggs did the Iron Maiden album covers. I will confess I love the song “Run to the Hills”

That was the moment I noticed the Eighties metal surge. I hadn’t been shopping much in the past year, go figure, but I began seeing shirts in window displays at mid-range women’s boutiques, folded on the tables next to $140 jeans. For years I’d watched Eighties nostalgia marching into Target, but this was a level beyond Prince and Blondie and Michael Jackson. This was Poison and Led Zeppelin and AC/DC, selling to Taylor Swift fans for $40 a pop. The shirts were soft and intentionally faded, simulating an old iron-on, although nobody ironed anymore.

I had a lot of those albums, back in the day. The record player lived in my room (my brother mostly listened to his Walk-Man), and I filled a white plastic crate with glossy cardboard portraits you could flip through. I dabbled in metal, worshipful little sister that I was, but my passion was Top 40. Lionel Richie with arms folded in a white suit, Madonna with her platinum blonde locks and black licorice bracelets lining her wrist, George Michael with his scruffy beard and black leather jacket, one cross dangling in his ear. They were like Mona Lisas to me.

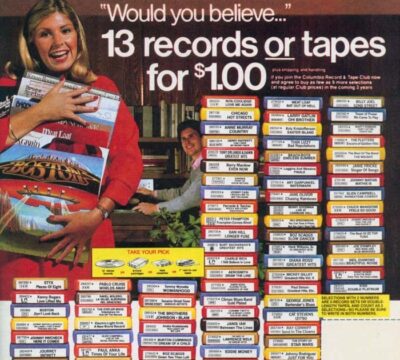

I signed up for the record and tape clubs, because all those albums for a buck were a steal, and then I’d bail on the full-price obligation, the monthly selections that arrived in cardboard. I’d learned your credit erases at 18 (or rather, you have no credit), so I ignored the overdue bills that arrived every other week, omen of the Visa and MasterCard bills to come, and I took out memberships under slightly different names, Sarah Hepla, Sara Hepulah, as albums turned to cassettes turned to CDs turned to VHS. As the teen movies understood, the line between hero and scoundrel was very thin.

The saga of Columbia House: Story for another time.

But the albums became the lost art. Through the Eighties and Nineties, I got swept up in new platforms, the big silver JamBox that could be unplugged from the electrical stream, or the Sanyo stereo system with a five-disc changer, like I was some oligarch. Relax and let the machine change the CDs for you. Those systems came with a remote control, so I could lie in bed with ankles crossed, skip a track, repeat a track. Turn it up.

But somewhere around the turn of the century, music went digital. Music disappeared, even as it became ubiquitous. CDs and cassettes looked suspiciously like landfill. All that plastic. CD towers clustered in second-hand stores, like skyscrapers from a forgotten skyline. And what emerged bright and shiny after the transition was the singular beauty of vinyl.

Almost Famous came out in 2000, a movie of deep nostalgia, and it included a voluptuous scene of the young Cameron Crowe stand-in tracing his fingers along the Bob Dylan and te Beach Boys and Joni Mitchell albums his sister left behind, as Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” plays in the background, a song so critical to the wandering soul of this movie that we hear a full two minutes before the incendiary opening of The Who’s Tommy. The scene is nearly sexual, his fingers moving with wonder and hunger, like a boy who will grow up to graze the hot spots of a woman’s back, searching for the same magic.

I bought a record player around 2013, in my late thirties. I was spending a lot of time in vintage stores, which sold albums on the cheap, and the player was an impulse purchase. It was the portable kind they used in schools, probably Seventies-era, and the guy I was seeing teased me for my lack of consumer discretion. He was an audiophile, who knew tones and speakers and shit, and here I was buying a rinky-dinky record player that announced every song with a high crackle, but that’s the kind of crappy record player I had as a little girl. I was not chasing the best sound. I was chasing the best feeling. I bought the Xanadu soundtrack, that futuristic art-deco cover, and I played it as the two of us lay in bed, losing ourselves in each other.

A place where nobody dared to go / The love that we came to know / They call it Xanadu

It was around 2018 when I bought a fancy Technics system. That guy had been gone for more than a year, but maybe I was trying to summon him, because he would have approved of that system. You could sit back on the couch and feel the music rise around you. The surround speakers were so complicated I had to hire a technician to install them. He kneeled on the brown shag carpet in a yellow polo shirt and khakis, whittling a wire with a pocket knife, first red, then black, and I could see how out-of-my-depths I’d been, trying to figure this out with the YouTube instructional video.

I met another guy around this time. He was the first man I’d been drawn to in so long I was practically covered in cobwebs, and he was much younger than me, which came as a surprise. He sat on my couch flipping through the vinyl albums like they were stone tablets. He picked up ELO’s Out of the Blue, that rainbow neon spaceship that looks like the game of Simon. I was straddling him on the couch, and I plucked the album from his hands.

“See what you missed, child of the Nineties? With your paltry CD collection, and flimsy inserts?” I creaked open the album as though I were spreading my thighs for him, and I watched as his dark sparkling eyes roamed the lyrics, and his fingers touched the glossy cardboard.

“You know they sell these at Urban Outfitters,” he said, his no-big-deal voice, and I smacked the album closed on his fingertips. How I adored a smart-ass.

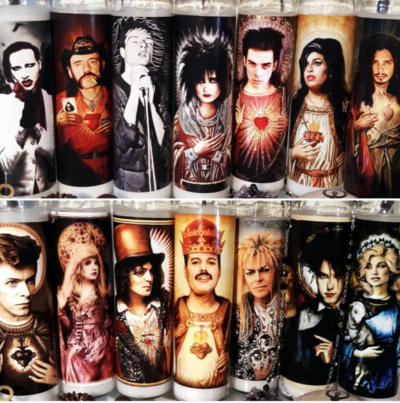

“Not the same thing,” I said, but mostly it was the same thing. My coy display was meant to illustrate the rare luxury of my youth, but that luxury had been available for purchase next to Japanese cosmetics and “Keep Calm and Carry On” merchandise for well over a decade. I’d hung a James Dean poster on the wall of my childhood bedroom, which I bought before I’d ever seen a James Dean film, so it’s not like I was unfamiliar with this phenomenon. Generations of kids growing up with John Lennon and Marilyn and Jim Belushi shirts, like dead pop-culture versions of the saints.

The younger guy lit up my world for a long time, but things were always tricky with him, and he’d grown scarce, and I’d gone shopping to take my mind off that. A pandemic check arrived, a good excuse for a splurge. I met a buddy at Josey Records, and we wore masks as we dug through rolled-up concert posters of REM and The Smiths and flipped through stacks of vinyl, and my cart filled with a miniature Ms. Pac-Man game, a Star magazine tabloid from 1988 (“George Michael broke my heart, Brooke Shields says”), an original bumper sticker from the Q102 Texxas Jam. I never even went to that concert (I was eleven), but I got a hit of nostalgia from the design I saw on the back of cars for years. That cool ombre coloring, yellow to burnt orange.

Nostalgia is a homesickness, at least according to the Google search I just did, and despite its enormous market, particularly among Gen Xers, nothing about nostalgia sounds healthy: “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to … some past period or irrecoverable condition.”

An excessively sentimental yearning to return to some irrecoverable condition. Ding-ding-ding. Some people call it an affliction, but it’s more like a job description for me.

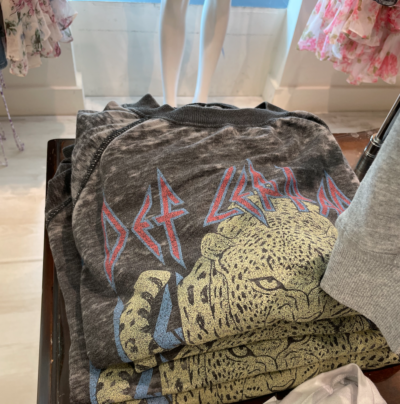

A few days later, I was grazing around uptown, and I ducked into a cutesy boutique, and I ran my fingers along the soft cotton shirts on the table, and there was the metal again. Def Leppard, KISS, Ozzy Osbourne.

“Can I help you?” asks a pretty millennial sales clerk in a ruffly sleeveless pantsuit.

“I have a question,” I say, plucking out a Def Leppard T-shirt with the pointy 80s font that reminds me of Gibson Flying V guitars. “Can you name a song by Def Leppard?”

“Umm, no.” She blushes. “But my boyfriend listens to them.”

“It’s weird, because my guess is that every girl who buys this shirt does not listen to this music, and I’m trying to figure out why the shirts are popular.”

A young woman who has been scraping hangers along a nearby rack turns to us. “So I have that shirt, and I couldn’t name a Def Leppard song. I know it’s stupid, but I liked the design.” Faded black, a growling leopard face. Not my deal, but whatever.

“Their early albums are good,” I tell her. “’Photograph‘ is a classic.” I don’t mention that “Pour Some Sugar on Me” is an assault from which we may never recover, but you can hardly blame a band for their success.

“I’m sure all the music is good,” says the pretty millennial sales clerk.

“It’s not,” I assure her. The Iron Maiden shirt is at the far end of the table, but I pick up an Ozzy Osbourne. “This is a very specific taste. I can’t say I’d recommend it. But a lot of the music — yeah, you’d like it.”

“I’m gonna listen to Def Leppard soon,” says the girl who owns the shirt.

“Photograph,” I tell her.

“Photograph,” she says back.

“Well, I consider my work done,” I tell them, and we each go back to what we had been doing. Two women scouring the merchandise for something, anything, and one woman pacing the floor till the moment she can ring them up at the cash register, consumer cycle complete.