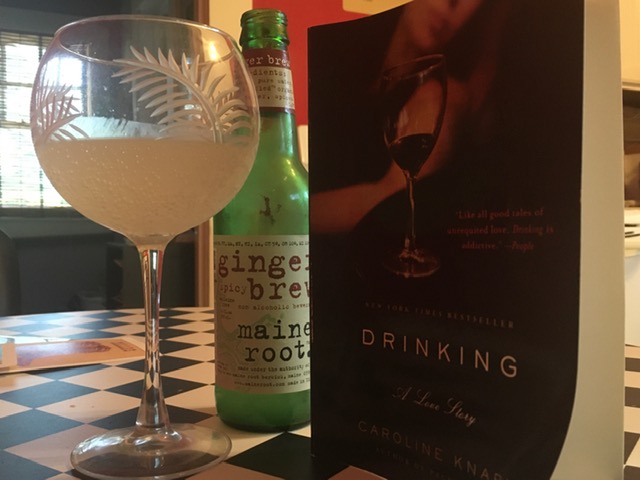

#3 Drinking: A Love Story

Caroline Knapp and the memoir that started it all

Part 3 of a 10-part series

I was 22 or 23. I was in Boston visiting my college roommate Tara Copp, who had an internship at the Globe. I was killing an afternoon by myself, and I was hungover, because I was always hungover, so I was wandering through a book store when the title caught my eye. “Drinking: A Love Story.” That sounded familiar.

I’d come to the neighborhood to visit Cheers, the bar from the TV show, but it was closed or I lost my nerve to go to a bar alone, I can’t remember which, so I sat on a soft patch of grass in a park and opened the book. “It happened this way,” the story began. “I fell in love and then, because the love was ruining everything I cared about, I had to fall out.”

Damn. That sounded familiar, too.

All my friends drank. Of course we did. We’d gone to a hard-partying state school at the affluent tail end of the 20th century. But I was starting to suspect there was something darker about the way I drank. I had blackouts. I fell down stairs. This must sound dramatic but what would have struck you about me at the age of 22 or 23 is that I looked like everyone else. I bought a skirt that day at Banana Republic. It was loose and rayon, and made me look thinner than I actually was. I listened to the Counting Crows. I watched “Ally McBeal.” I only meant to dip a toe in the book that afternoon, but I fell right in. From chapter one:

“I drank when I was happy and I drank when I was anxious and I drank when I was bored and I drank when I was depressed, which was often.”

Shit yes, that was familiar. I’d never heard anyone talk like this, with such intimacy and precision, like some expert violinist had tightened the bow strings on my jangly, loose thoughts at 3am. And then I arrived at this:

“There are moments as an active alcoholic where you do know, where in a flash of clarity you grasp that alcohol is the central problem, a kind of liquid glue that gums up all the internal gears and keeps you stuck.”

I put the book face-down. A kind of liquid glue that gums up all the internal gears. Page fucking four, and she’d nailed me.

This was the summer of 1997, the year the book became a bestseller and launched a career for the author Caroline Knapp that would be far too short. The memoir was in a boom time. Book nerds and literary critics should feel free to correct me, but I think of the late-20th-century memoir boom as beginning with the one-two punch of Mary Karr’s “The Liar’s Club” in 1995, followed by Frank McCourt’s “Angela’s Ashes” in 1996, two barnburners that brought us inside the kind of chaotic, hard-drinking families the talk shows were calling “dysfunctional” and the talk therapists were calling “abusive” or “traumatic” but for some folks had just been life. The late Nineties coincided with the rise of Internet, where live journals and “online diaries” and blogs were delving into these kind of domestic battlegrounds, and it’s only in retrospect I see all of these as related, a longing for the first-person voice as technology pushed us farther away.

I read Knapp’s book once, and then again. I gave it to friends. I quit drinking at 25, started up again at 26, read the book at 30, 33, coming back to it like a mountain I did not want to climb but could not leave. Each time I saw more of myself. I’d never been pulled over for drunk driving the first time I read the book. Ten years later, I’d been pulled over twice. Knapp described red dots around her eyes from puking in the morning, broken blood vessels, and the first time I read that, I thought how gruesome, and later I thought how familiar.

I was 35 when I quit drinking. I was 40 when my first book came out, so clearly inspired by her memoir that I might as well have called it, “Blackout: Also a drinking love story.” Knapp died in 2002 at the age of 42. Lung cancer, dammit, the same disease that took her father. I was proud when any review of my book mentioned her. Maybe I was biting her style, but I liked to think I was carrying her torch, that we all were: Mary Karr and Leslie Jamison and Glennon Doyle and Ann Dowsett Johnson and Laura McKowen and Holly Whitaker and Amanda Ward and Jardine Libaire and all of us who stand in the long shadow that stretches out from the woman who placed a book on the shelf that was not about men’s drinking, which had been such an endless preoccupation of 20th century fiction. But this was a memoir. It was a woman’s story. It was a love story.